How Predictive Models Can Help Social Impact Organizations

Predictive modeling has become one of the most talked-about tools in quantitative research and data science. As nonprofits, governments, and social-impact organizations look for ways to anticipate needs, allocate resources more efficiently, and understand patterns that influence community well-being, predictive modeling can be a powerful tool for research. Our goal in this post is to highlight where predictive modeling fits in the context of other research tools, how it can be used in social impact research, and when to use it appropriately. As is true with all statistical tools, thoughtful use, rigorous testing, and careful interpretation are more important than the technologies you use to complete the task.

Predictive Modeling 101: Where It Fits in the Quantitative Toolkit

Predictive modeling is the process of using historical data to forecast future outcomes. It can help answer questions like:

Who is most likely to benefit from this program?

Where might the next surge in service demand occur?

What factors predict unsafe conditions, recidivism, dropout risk, or health crises?

It’s important to recognize that predictive modeling is different from other types of research.

-

Descriptive statistics summarize what is happening in the data right now or what has happened in the past. They include counts, percentages, averages, trends over time, and basic comparisons across groups. These measures describe patterns and provide a snapshot of current conditions in your data.

Examples:

What percentage of program participants completed training?

How many families were served last quarter?

What is the average change in test scores compared to last year?

-

This type of modeling attempts to determine whether one thing actually causes another. The common saying “correlation isn’t causation” is an important reminder that related variables must meet strict modeling and data collection requirements before we can determine a causal relationship with confidence. This statistical framework is common in economics, education research, public health, and program evaluation. Common methods include randomized controlled trials (RCTs), experiments, and specialized statistical techniques that isolate cause-and-effect relationships.

Examples:

Did the after-school program improve reading scores?

Did expanding rental assistance reduce homelessness?

Did the job-training program increase earnings?

-

Predictive modeling uses historical data to forecast future outcomes or the likelihood that specific individuals, communities, or conditions will experience certain events. The goal is to use associations in the data to see what accounts for variation between your predictor (X) variables and your outcome (Y) variable.

A key takeaway from this introduction is that prediction is not causation. Predictive models help allocate resources and prepare for expected needs, but they do not explain root causes or prove that programs work. That being said, when integrated with evaluation and community knowledge, predictive analytics can become a powerful tool for understanding the needs of your organization’s stakeholders.

There are many techniques for predictive modeling from traditional methods like linear regression to more modern machine learning and AI models. For the size and structure of most datasets used in social-impact research, well-designed regression models can be surprisingly accurate. Any model you choose to work with will come with its own set of design choices and mathematical constraints that directly affect the validity of model predictions. Because of this, it is important to consult with statisticians or data scientists when building, testing, and interpreting predictive models. Their guidance ensures that the model is appropriately chosen, assumptions are checked, and results are communicated responsibly, preserving both the rigor and integrity of your research.

Example: Modeling Crime Data Using Predictive Models and GIS

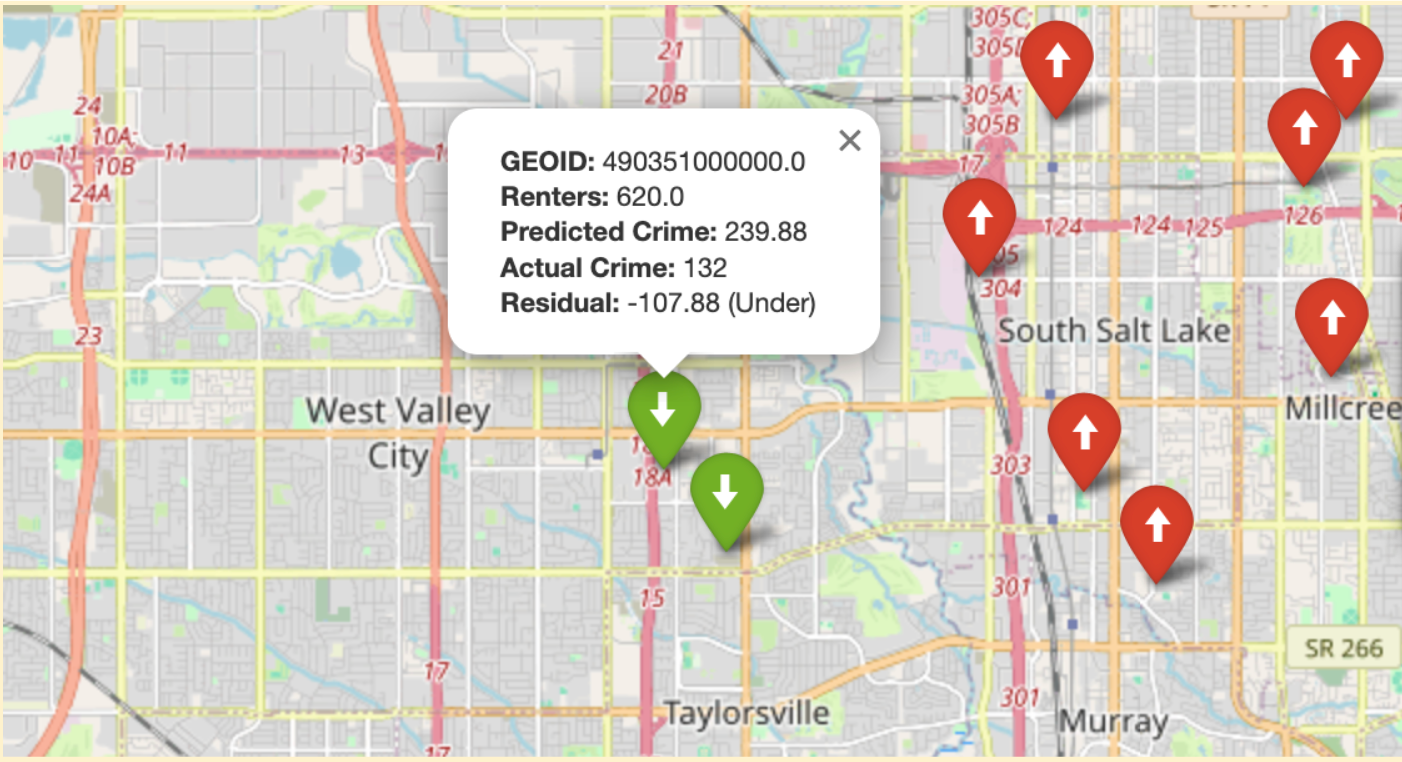

A recent project at Socio illustrates how predictive modeling can add meaningful insight even when long-term forecasting isn’t possible. We worked with a proprietary, statewide crime dataset that standardized hundreds of law-enforcement sources across Utah. The data had more than 70 potential predictors including economic conditions, demographic variables, land-use and zoning information, infrastructure details, and environmental characteristics. By building a predictive model on this dataset, we were able to estimate the level of crime that should be expected in each area given its underlying conditions.

Although we did not have sufficient time-series data to forecast future crime, the model allowed us to predict crime rates in each census block group given the economic, demographic, and geographic variables available in the data. The model created a baseline of “expected” crime risk, enabling us to see which neighborhoods were over-performing (safer than predicted) or under-performing (higher crime than expected) relative to their structural characteristics. This helped shift the conversation from raw crime counts to a more nuanced understanding of where community strengths or stressors may exist. These predictions offer important insights for policy makers and developers to determine how to plan for safer growth in Utah cities.

By combining these models with GIS mapping, cities can visualize:

“hot spots” where crime risk is concentrated

emerging trends that signal shifting safety needs

neighborhoods where environmental conditions increase vulnerability

areas where targeted interventions may have the greatest effect

This selected GIS graphic from our research shows an example of a Census Block that had a lower than predicted Total Crime Index (proprietary measure) based on the economic and demographic characteristics of the area. Modeling in this way allowed us to see which areas had lower or higher crime rates than the model predicted. The next step was to investigate those communities qualitatively for deeper findings.

It’s important to reiterate that these models can’t tell us why crime occurs or what factors are causing crime. Only causal inference using the appropriate data and statistical techniques could give us those types of insights. But when combined with community input, qualitative research, and program evaluation, these insights can help leaders design more efficient strategies: improving lighting, adjusting patrol routes, supporting local community organizations, or revisiting zoning and infrastructure needs.

Other Real-Life Examples Across the Social Sector

Predictive modeling has been used in many core public-service and nonprofit functions. Although the technical details vary across contexts, the underlying goal usually relates to using historical data to identify emerging needs, anticipate risks, and allocate resources more effectively. Below are several domains where predictive analytics has demonstrated practical value and continues to evolve in meaningful ways.

1. Homelessness Prevention

Several jurisdictions have incorporated predictive analytics into homelessness prevention efforts. Research funded by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) has shown that administrative data can be used to identify individuals at elevated risk of entering homelessness (Rodriguez & Fudge 2023).

2. Education and Early Warning Systems

Early warning systems (EWS) have become a common component of educational data infrastructures nationwide. These systems rely on predictive indicators like chronic absenteeism, course failures, and behavioral incidents to identify students who may be at risk of dropping out. Empirical studies consistently demonstrate that such indicators can predict dropout risk several years in advance (Allensworth & Easton 2007).

3. Nonprofit Resource Planning

Predictive analytics has also been integrated into nonprofit operations and logistics. Food banks and emergency nutrition organizations use demand forecasting models to optimize procurement schedules and distribution routes, especially during seasonal shifts or crisis periods (Gundersen et al. 2017).

These examples can hopefully inspire ideas on how you can implement predictive modeling in your organization’s research and evaluation work. Awareness of these methods can be a powerful gateway to new research-based insights that can improve social impact solutions.

When (and When Not) to Use Predictive Models

Predictive modeling is a valuable analytical tool, but it is not universally appropriate and should not be treated as a substitute for careful research design or community-informed decision-making. As scholars in data science and public policy consistently emphasize, predictive models are only as reliable as the data, assumptions, and social context in which they operate (Kleinberg et al. 2015).

Predictive modeling is most effective under conditions that support reliable estimation:

When data is relatively complete, consistent, and accurately measured. Predictive modeling depends on stable patterns; missing data or measurement errors can significantly reduce accuracy.

When the question is forward-looking. These methods answer “What is likely to happen next?” rather than causal questions like “Did this intervention work?”

When the goal is planning or resource allocation. Forecasting demand for shelters, clinics, or educational support are common examples.

When local stakeholders can help interpret results. Community insight reduces the risk of misinterpretation and supports responsible use.

There are several conceptual, statistical, and practical circumstances where predictive modeling is inappropriate and risks generating misleading or harmful conclusions. It should be avoided when:

You need to understand why something is happening. Prediction cannot establish cause and effect.

The dataset is too small to support stable predictions. Small sample sizes lead to unstable predictions and low accuracy. Models trained on small datasets often perform well during testing but fail when applied to real-world situations because they've learned patterns that don't actually exist.

When the data is sparse, patchy, or structurally biased. Predictive models trained on incomplete datasets, under-represented groups, or historically inequitable data will often replicate and amplify those biases

When relationships between variables are unstable or highly contextual. If the real-world conditions creating the data are rapidly changing (due to policy shifts, economic shocks, public health crises, or environmental changes), predictive models may fail because past patterns no longer resemble present conditions.

When measurement error is high. If key variables are self-reported, inconsistently recorded, or defined differently across systems, the resulting noise can drown out the model’s ability to detect patterns.

Ultimately, predictive modeling is most powerful when it is used alongside qualitative insight, thoughtful program evaluation, and human expertise.

Conclusion

There are limits to the usefulness of modeling. Statistical models won’t build your organization, they can’t directly serve your stakeholders, and they don’t implement programs for you. With all that said, statistical models can be very powerful for guiding decisions. They are tools that can illuminate patterns that are otherwise hard to detect, highlight anomalies that deserve attention, or surface operational insights that would be easy to overlook in day-to-day programming.

If you’re interested in seeing how to make the most of your data, please contact us or reach out to a member of our Socio team directly to learn more about Socio and our data science services.

References

Allensworth, Elaine M., and John Q. Easton. 2007. What Matters for Staying On-Track and Graduating in Chicago Public High Schools. Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Gundersen, Craig, et al. 2017. “Food Bank Demand Forecasting and Operational Planning.” Journal of Humanitarian Logistics and Supply Chain Management.

Kleinberg, Jon, Jens Ludwig, Sendhil Mullainathan, and Ziad Obermeyer. 2015. “Prediction Policy Problems.” American Economic Review 105(5): 491–495.

Rodriguez, Jason, and Margaret Fudge. 2023. Risk Modeling for Homelessness Prevention. U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research.