Housing First and the Economics of Stability: Lessons from New Path

Homelessness represents a complex social problem that reflects broader structural inequalities in housing markets, healthcare access, and economic opportunity. From a sociological perspective, chronic homelessness cannot be understood simply as an individual failure, but rather as the outcome of systemic barriers that prevent vulnerable populations from accessing stable housing and supportive services. Guest author, Mcallister Hall, from the Idaho Policy Institute, presents one policy approach that has proven effective in addressing these social challenges.

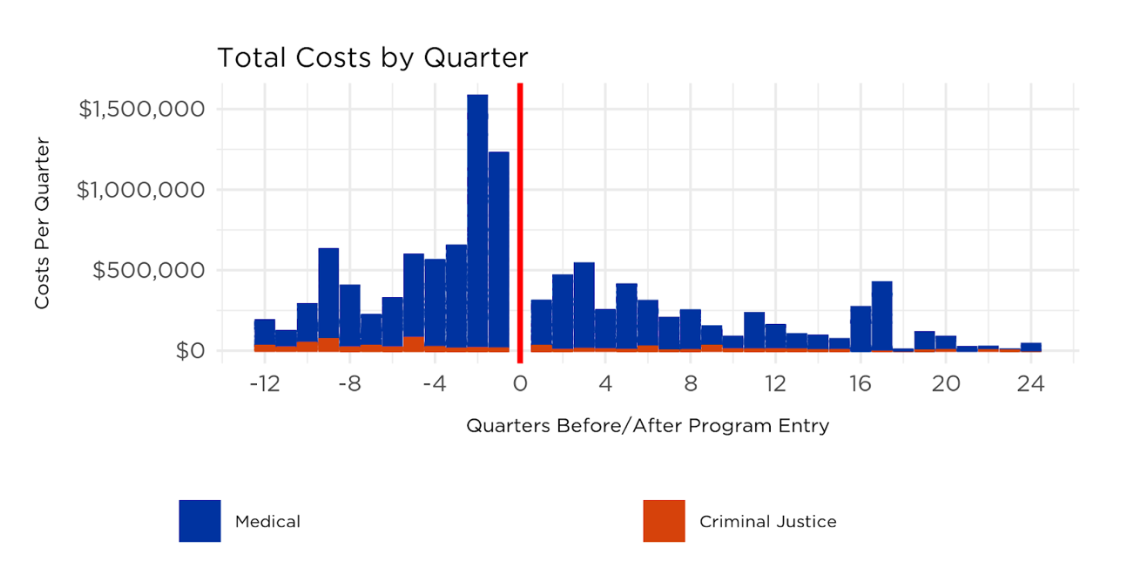

While the chronically homeless are only about 15% of all homeless, they account for the majority of the resources directed addressing homelessness as a social problem. Each year of homelessness significantly decreases individuals’ quality of life and physical and mental stability. This instability leads to increased use of public services, like regular visits to the emergency department or frequent overnight stays in local jails.

Housing First is often implemented as part of permanent supportive housing (PSH) programs designed to address the human needs associated with chronic homelessness as well as reduce its social costs.

PSH prioritizes unconditionally-available, stable, long-term housing above other public services in efforts to end chronic homelessness.Effective PSHs address human needs by including case management services as well as easy access to mental health support, treatment for substance dependency, and medical care. While these support services are available in Housing First communities, they are not conditions of residence. This is critical because evidence shows that the availability of these services absent a requirement to use them actually leads to higher levels of utilization and longer-term well-being.

The long-term stability created by PSH programs leads to substantial direct and indirect savings for communities. There are direct savings because the costs associated with Housing First programs are lower than when homelessness is addressed in more traditional ways. Indirect savings accrue as well because of the associated reduction in crime.

The benefits of PSH is illustrated by New Path Community Housing’s first multi-unit PSH program, in Boise, Idaho which began in November 2018. New Path’s program includes a single-site, 40-unit complex with support services. Participants include Ada County residents previously experiencing long-term homelessness and frequent interaction with reactive public services (i.e., emergency health care and the criminal justice system). A total of 100 people have entered into New Path programming since its launch in November 2018.

The first year saw a cost avoidance of $1.38 million. By year six, the total calculated savings/cost avoidance for the project reached $11.1 million. As indicated by the figure below, the costs of homelessness in the community was on an increasing trajectory before New Path’s beginning. The program immediately reduced costs, and, aside from two residents having unexpected long hospital stays, costs to the community have continued to decrease.

The success of New Path has already informed future Housing First projects in Boise. Valor Pointe, a 27-unit apartment complex offering health care, mental health counseling and substance abuse treatment opened its doors to Ada County’s most vulnerable veterans experiencing homelessness in August 2020. In addition, a group of community partners is collaborating on three new projects in varying stages of development that will bring 193 new single-site PSH units within the next several years, including 48 units that will be for families with children.

This blogpost is an abridgment of the sixth annual New Path Evaluation. The full report can be found here.

To learn more about the New Path Community Housing Evaluation and read past evaluations please visit Idaho Policy Institute’s website.

The Socio Take:

The Housing First model challenges traditional approaches to homelessness that try to address mental health and substance use issues before accessing housing. This paradigm shift recognizes what sociologists call the "fundamental cause" theory—that stable housing is a prerequisite social determinant that enables individuals to address other challenges in their lives. Without this foundation, attempts to treat health issues or maintain employment become significantly more difficult.

Chronic homelessness also illustrates the concept of cumulative disadvantage, where initial setbacks compound over time. Each year without stable housing erodes physical and mental health, making it progressively harder to exit homelessness. This cycle creates what sociologists term a "revolving door" between emergency services, jails, and the streets—a pattern that is both costly to communities and destructive to individuals.

Furthermore, the disproportionate resource utilization by chronically homeless individuals reflects a broader principle in public policy: reactive services (emergency rooms, jails) are more expensive and less effective than proactive interventions (stable housing with support services). This pattern reveals how social policy choices shape not only individual outcomes but also the efficient allocation of community resources.

The success of programs like New Path demonstrates that addressing chronic homelessness requires an interdisciplinary approach that integrates insights from sociology, psychology, economics, and healthcare. By understanding both the individual experiences and community-wide impacts of homelessness, policymakers can develop more effective solutions. While New Path has proven successful in Boise, it's important to recognize that contextual factors—such as local housing markets, available resources, and population characteristics—vary across communities. A sociological framework helps identify which factors are most relevant in a given context, enabling communities to adapt evidence-based models like Housing First to their specific circumstances and create interventions with lasting impact.

The United States Interagency Council on Homelessness. (2015). Opening doors: Federal strategic plan to end homelessness. Washington, DC.

Donovan, S., and Shinseki, E. (2013). Homelessness is a public health issue. American Journal of Public Health, 103(2), Supp. 2, S180.

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (July 2014). Housing First in permanent supportive housing brief - HUD Exchange. Web. 19 Apr. 2016.

Silleti, L. (2005). The costs and benefits of supportive housing: A research paper. Center for Urban Initiatives and Research. University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee.

Tsemberis, S., Gulcur, L., & Nakae, M. (2004). Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 651-656.

Crossgrove Fry, V., McGinnis-Brown, L., Hall, M., & Spalding, K. (2025). New Path Community Housing annual evaluation 2024. Idaho Policy Institute. Boise, ID: Boise State University.