The Heart and Soul of Social Good—Part 2: A (Socio)logical Perspective

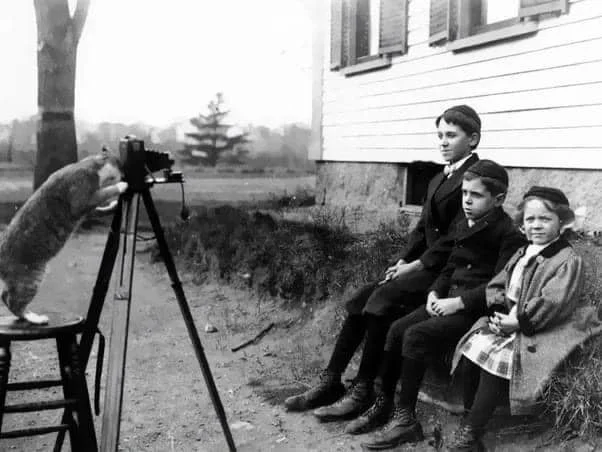

US History Uncovered [1909]

Sociology is about studying and understanding social influence.

Often, the work of sociologists can make invisible social influences visible, and can help understand irrational behavior as rational. For example, why would anyone join a gang (Venkatesh 2008)? Under what circumstances might a top student choose not to apply to a top university (Jeffrey and Gibbs 2022)? Why do Americans care deeply about welfare reform, yet nothing has meaningfully changed in 30 years (Desmond 2023, McCall 2013)?

“Thinking sociologically means...examining closely how social contexts can constrain opportunities and shape the outcomes we all care about.”

Thinking sociologically means contemplating how social connectivity can promote patterns of human experience that create meaning. It means examining closely how social contexts can constrain opportunities and shape the outcomes we all care about—socioeconomic stability, socio-emotional well-being, belonging and connection with others (Grusky 2018). The families, communities, and culture we come from can profoundly influence us in ways that often go unmeasured, or even unnoticed altogether.

A sociological perspective can add focus to social problems that plague the world—poverty, crime, pollution, economic failure, war and violence, and emphasize the role of factors like race, class, and gender in the inequalities we see in social institutions like education, government, health care, family, and the criminal justice system (Conley 2021).

And finally, sociologists are trained to test these perspectives using a variety of techniques, including both quantitative (e.g., surveys, administrative data) and qualitative (e.g., interviews, observations) research methods (Kenneavy et al, 2022). This is especially important because, for sociologists and non-sociologists alike, it is all-too-easy to project our own social realities onto others. So much of what we experience in our social lives feels “natural” and, we therefore assume, likely similar to the experiences of others. For organizations seeking to do social good, for example, this can cause decision-makers to drastically misunderstand the experiences of those they serve, report to, or even employ.

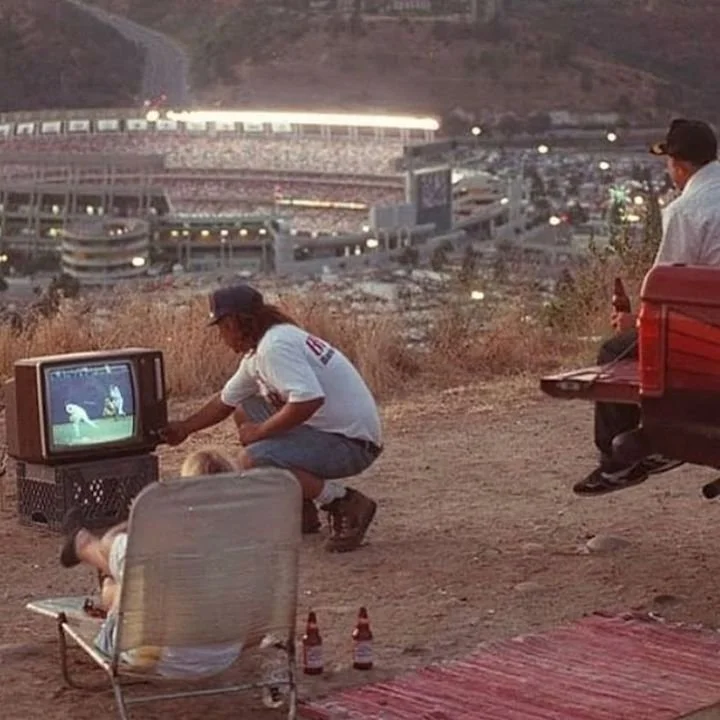

US History Uncovered [1992]

Where are the sociologists?

In part 1 we discussed the complex and wide ranging world of social good, as well as the many ideas, practices, and innovations being employed in its pursuit. So, given sociology’s focus on understanding social life it seems that sociologists would be well-equipped to both guide and measure such endeavors. Yet, outside of journal publications (see Rawhauser et al. 2019; Galluccio 2023; Child 2020), sociologists have not been particularly involved. Why?

First, despite a few bright sparks in the early 2000s and a variety of social justice advocacy efforts recently, the effort to apply sociology professionally has not been as prominent as it has been in other disciplines, such as economics, political science or social work. There is no easily-recognizable vocation for sociologists beyond the academy where organizations might find the theoretical, conceptual or analytic help they might need. We might, then, attribute the lack of sociologists to limited supply.

However, there is another related problem. Because so many important social factors go unseen, even the need for sociological thinking can go unnoticed. In other words, it often takes a sociologist to raise the kinds of important questions that a sociologist might be uniquely equipped to answer, and with relatively fewer sociologically-trained leaders in the private sector (compared to MBAs, Economics PhDs, etc.), there has historically been limited demand for applied sociologists, as well.

Is this a problem? Yes. For example, one significant issue that has already surfaced is impact washing, or the practice of using social impact efforts for commercial purposes but with little regard for actual impact. Relatedly, doing no measurable harm is different than doing measurable good, and many corporate actors release ESG disclosures and sustainability reports as a way to check boxes rather than promote meaningful impact (Serafeim 2020). We argue that without sociology, the ideas, practices, and innovations in this field (see Part 1), are less likely to produce meaningful social good. In short, an effort this important needs a sociological partner.

Applying a (socio)logical perspective

An example:

Picture the worst kid you knew in middle school—that disruptive kid that everyone understood as the “bully.” Think Sid in Toy Story (fan theory rabbit hole here).

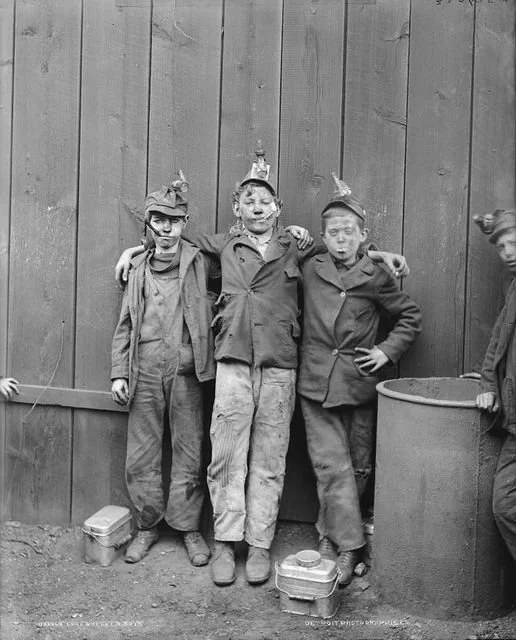

US History Uncovered [1900s];

The conventional approach to such a problem would be to focus on this kid's poor choices, such as his lack of self-control and his basic struggles to communicate frustration effectively. One conventional solution is school discipline: detention, out-of-school suspension, and related punishments. These approaches take an individual perspective on the problem of the bully’s behavior—the intervention is focused on the student.

But the bully’s problems occur in school, and this environment is not just his responsibility to navigate. In some ways, this student might represent a failure of the school to control kids like them or to provide for some broader, unmet need. Efforts, therefore, might seek to hold teachers more accountable, get them to push kids like this to perform better in class (and state-wide tests), and minimize disruption in the classroom. More teacher mentoring, stricter classroom policies, and greater teacher engagement with parents could help address the problem. This is an institutional perspective—the intervention is focused on the school, more specifically the teachers. It is more sociological than the first approach and accounts for additional factors, but it still falls short.

Both perspectives understand that a disruptive student is embedded in a social world, and both have a role to play in creating a better reality for this child, for the school, and maybe even for the larger society.

But the individual and the institutional perspectives likely don’t know much about the bully. If a student spends 83% of his waking hours outside of school (Downey and Gibbs 2010), there are invisible influences on a student that both perspectives fail to capture. Furthermore, if this example is in middle school, this student is about 13 years old. By the time we are introduced to the student, they have experienced over a decade of life. The experiences and constraints that a student brings to school are hard to discern in the fleeting interactions students, teachers, administrators have with their pupils (see Downey 2020).

A more holistic approach

Thinking more broadly about “the bully,” we know, for example, that there are a large share of troubled kids at this age that have had multiple Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs)—exposure to home violence and abuse, family instability, and general trauma. ACEs predict suspensions (Pierce, Jones and Gibbs 2023) and are linked to less engagement with school and a decreased likelihood of attending college (Otero 2021). In this example, knowing something about trauma is not uniquely sociological (psychology, for instance, has much to contribute here), but looking more holistically at the disruptive student’s social contexts outside of the school institution is.

What it all means

Just as interventions around behavior like this student’s are often limited to the most visible factors—a picture that is insufficient, incomplete, or just too far downstream—organizations of all kinds may tend toward solutions that are based on what’s easily visible but not necessarily most important or effective. For organizations focused on social good, such as impact investors, social enterprises, and nonprofits, a holistic understanding of the social worlds in which people are embedded, as well as the constraints they often experience, is crucial. Lacking awareness of these factors and the methods that can measure them, interventions are likely to be considerably less effective, leading to wasted resources and even, in some extreme cases, unforeseen harm.

For an actual example, Socio has consulted with university administrators to help support first-generation college students (students whose parents or caregivers did not graduate from college). Many universities are beginning to marshal significant resources to help this often-marginalized student population find their way to the American Dream. But doing so effectively requires a more holistic understanding of the challenges first-gen students face.

“[Organizations] may find themselves helping the wrong populations, or helping the right populations poorly.”

In our work we have found how important it is, for instance, to clarify what is meant by “first-generation college students'' to ensure we are tackling the right problem. On the one hand, just knowing if a student has parents who didn’t go to college or didn’t complete college may not be enough because it doesn't tell you why—some students come from wealthy homes of parents who dropped out of college. On the other hand, not all students whose parents graduated from college have the resources needed to be successful in college themselves. The issue is far from straightforward.

In this small example, one can see, then, how interventions in this area might fall short without a complete enough picture. Without the necessary frameworks and measures to reveal these students’ realities, universities may find themselves helping the wrong populations, or helping the right populations poorly.

In Part 3, we will conclude with several more examples of how a sociological perspective can benefit the world of social good. We will share specific experiences from our own work, as well as compelling examples from sociological literature, including such things as the effect of protests on businesses, the increasingly blurred lines between for-profit and nonprofit sectors, and the mixing of private and public logics in the world of Social Impact Bonds.