The Heart and Soul of Social Good—Part 3: The Science and Art of Social Impact

To have impact at scale, you must understand people at scale.

We showed in part 1 that the world of social impact is varied and often extremely complex. In part 2 we introduced some of the ways in which a sociological way of thinking can help make sense of efforts to produce “social good” and, more importantly, can provide a more holistic approach to doing so. Here we want to build on that foundation by getting more specific—how exactly can sociology inform efforts to produce positive social impacts? What tools, findings, and frameworks can we draw on to plan, execute, and evaluate our efforts to improve the social world?

First we will give a quick overview of a few of the methods sociologists use to reveal hard-to-see social realities. Then we’ll give a small taste of the numberless insights available in the body of social science literature. And finally we’ll discuss how a “sociological imagination” can transform the way we approach social impact in any of its forms.

How to Measure Impact

The famed French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu once said that “The function of sociology, as of every science, is to reveal that which is hidden.” And surely sociology does this, but with the caveats that 1. Human social behavior is endlessly complex and 2. That many of its most central elements resist the kind of objectivity we often like to rely on. Neil deGrasse Tyson once tweeted that “In science, when human behavior enters the equation, things go nonlinear. That’s why Physics is easy and Sociology is hard.” Now, whether or not physics is easy is a topic for another day, but we can agree that sociology is hard. Because of this fact, sociologists rely on a number of different methods to capture and analyze complex social phenomena.

“The function of sociology, as of every science, is to reveal that which is hidden.”

Many things can be measured quantitatively. For example, we can analyze data from surveys, school test results, the census, or other available datasets and learn quite interesting things about people. And while analysis on existing data can be extremely productive, involving a social scientist in shaping measures before they are applied can increase the likelihood that they properly track the metrics that matter most. This is especially important in the world of social impact where interventions are implemented with specific goals in mind, and which can also have unforeseen and far-reaching negative effects.

Much of the social world, though, can’t be quantified so cleanly. To capture these things we use qualitative methods like interviews and ethnographic observations, which sacrifice some of the objectivity (real or perceived) that we associate with numerical data in favor of thick, contextual data about people’s lived realities. Then we code for themes and analyze in search of informative patterns.

To oversimplify somewhat, quantitative methods tend to provide a general understanding of a lot of people, while qualitative methods favor a deeper understanding of a smaller group. Both are extremely valuable and are often used in tandem.

What do we already know?

In addition to methods of gathering and analyzing data, sociologists have the benefit of familiarity with decades of valuable social science findings. Similar to the way a doctor can listen to a patient list symptoms and begin to develop an idea of causes and potential solutions based on their understanding of past medical research, we can often help organizations identify and solve problems by drawing on the findings and frameworks established in social science literature.

“Similar to the way a doctor can listen to a patient list symptoms and begin to develop an idea of causes and potential solutions based on their understanding of past medical research, we can often help organizations identify and solve problems by drawing on the findings and frameworks established in social science literature.”

For example, are you a for-profit company operating with a nonprofit mission and wondering how to align your profit-seeking and social good motives? This article found some interesting ways in which people in such organizations “framed away” the potential paradox of “doing well by doing good.” Reading it may help you better understand yourself and your organization or even lead to new ways of doing work. And this article demonstrated how, even in organizations that blur the lines between nonprofit and for-profit, sector-specific constraints can still hinder their ability to move and innovate. Some constraints are regulatory, but others deal more with norms and culture and are harder to see at first glance. Understanding this can help you as you challenge the status quo in and out of your company.

Do you feel like your org needs an R&D department but aren’t sure why? Literature on institutional logics and isomorphism will open your eyes to the ways in which organizational fields (essentially your peer organizations) can lead to irrational behavior in the pursuit of legitimacy (basically peer pressure between organizations).

Interested in using protests to change corporate behavior? Here are some helpful insights. Looking to get involved with Social Impact Bonds? There’s a whole literature on the topic, but this is a good place to start.

In other words, while your circumstances may be unique in many ways, there is often a data-backed sociological framework available to help explain the social forces at work, empowering you to better navigate your specific challenges.

Unfortunately, for reasons we’ve already discussed in this series, sociologists have been so busy doing the research that virtually nobody has heard about it. We’re hoping to change that.

A Perspective of Perspectives (and a story)

In addition to useful research methods and a massive body of underutilized findings and frameworks, sociology can also provide what some have called a Sociological Imagination. I’ll illustrate what this means with a personal story.

Years ago I was invited to consult a team of skilled design engineers from a North American university. Our aim was to design farming equipment for cassava farmers deep in the Brazilian Amazon, and to do so a way that would be economically, environmentally, and socially sustainable (a.k.a. Triple Bottom Line). In other words, the team had decided it would not be enough to design a machine that remained economically viable and avoided negative environmental externalities, it also needed to respond to the local social context—to give the farmers a solution that would be intuitive, culturally sensitive, and that they could feel ownership over. This way they might avoid the mistakes of similarly well-intentioned projects that are quickly relegated to the junk heap or, much worse, have negative downstream social impacts.

As we’ve already discussed, social and cultural factors are often extremely difficult to capture quantitatively, especially from the outside. So we spent nearly two years engaging local stakeholders in a process we came to call “co-design” (short for “collaborative design”) in which engineers, farmers, local politicians, and rural entrepreneurs together made up the project’s “design team” so they could shape it from the inside.

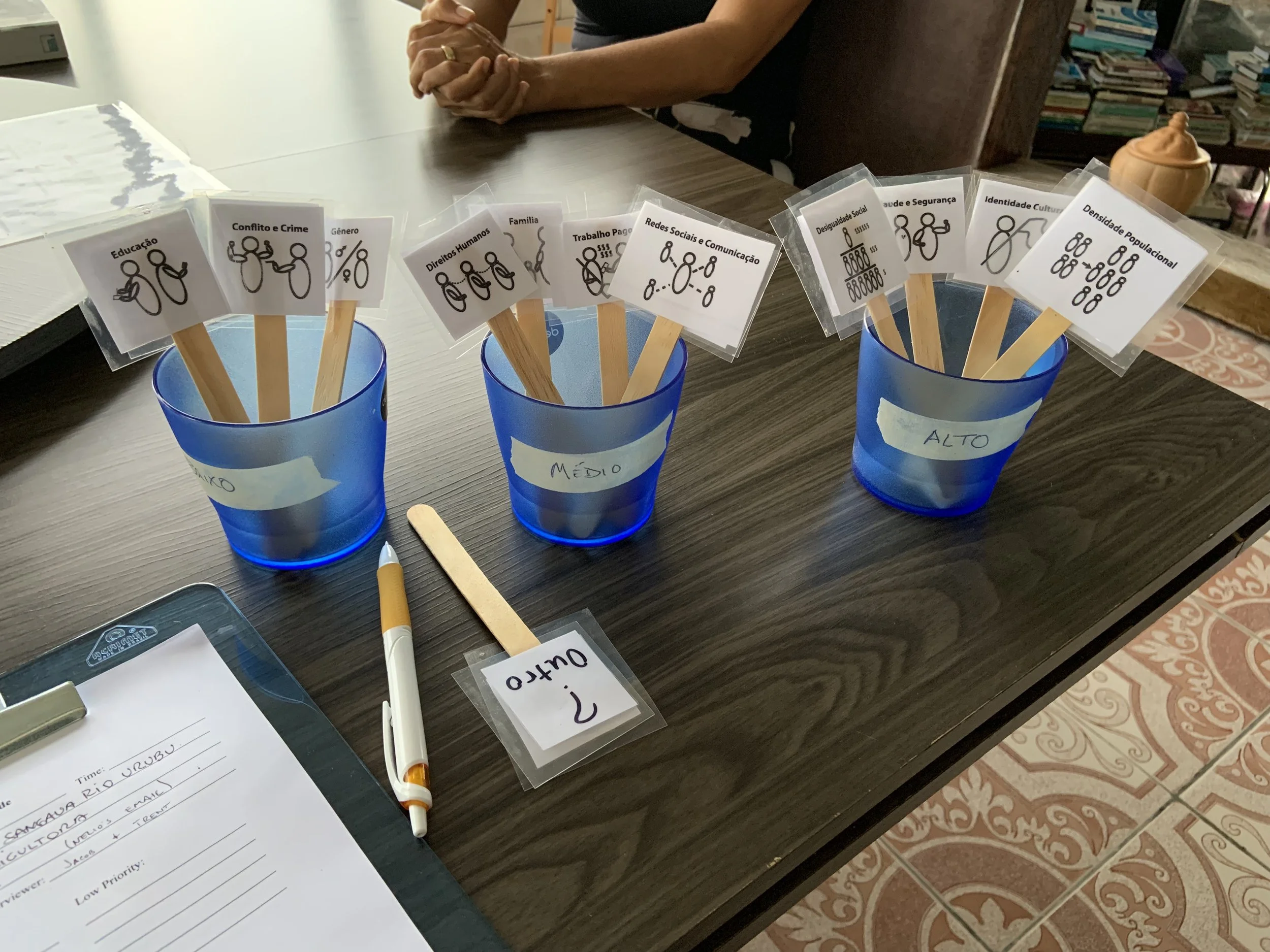

Through observations, interviews, and even a game that we created, we learned a few important things:

The codesign game allowed us to discuss and rank a range of potential impact areas with stakeholders of varied backgrounds.

Many important social factors—such as tradition, family time, and spiritual connection—did, in fact, resist quantification. Others were much easier to model, like financial well-being and time savings.

Distinct “logics,” or ways of making sense of the world and measuring success, became apparent. I categorized them as engineering, modernizing, and traditional.

Engineering—seeks efficiency; success is measurable impact.

Modernizing—seeks progress; success is financial well-being and time saved.

Traditional—seeks conservation; success is closeness to tradition and family.

Due to their specialized skillset, without which the project could not be completed, the engineers had the de facto “last say” on most major decisions.

Because of compatibility between the engineering and modernizing logics (mainly that the priorities of the modernizing logic were quantifiable and therefore able to be framed as “success” in the engineering logic) that was not shared with the traditional logic, the project struggled to account for the latter’s priorities.

In truth, I was not a neutral outside observer. I was an active part of the design team and represented my own particular, sociological logic. Because of this, I was able to convey these concerns to the engineers and, to some extent, help them deprioritize their own definition of success in order to better account for all local priorities. The project became less about measuring specific outputs (e.g. time saved) and more about the subjective push-and-pull of collaboration.

Designing for Impact

Having an impact at scale requires understanding people at scale. It requires making the unseen seen, the irrational rational.

When planning for social impact, leaders consciously or unconsciously choose which perspectives will get a seat at the design table. Furthermore, unseen constraints may determine which perspectives are heard and which are not.

Sociologists can, of course, help measure outcomes and can draw on past research to consult from outside. But where we do our best work is from the inside, as part of the design team, where we can help you make sure that all relevant voices are heard and that all relevant markers are being factored into your definition of success.

In the past, social impact leaders have often had to guess at these things, and many have managed to create incredible outcomes in spite of all obstacles. Many others may have hit roadblocks that made them wonder, in some form or another, “Where are the sociologists?” Well, now you know where to find us and what we can bring to the table.